Amelia Hill @byameliahill

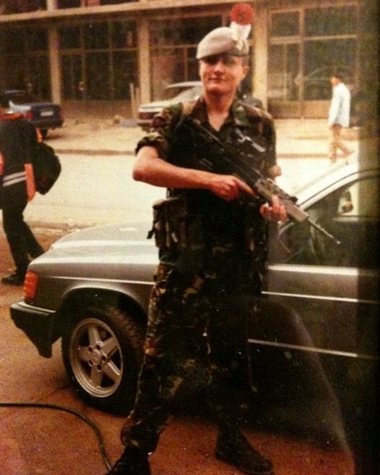

Wayne Sharrocks as an 18-year-old serving in Afghanistan. He joined the army on his 17th birthday. Photograph: Sharrocks family

Wayne Sharrocks as an 18-year-old serving in Afghanistan. He joined the army on his 17th birthday. Photograph: Sharrocks family

Recruiting children aged 16 and 17 into the British army places them at greater risk of death, injury and long-term mental health problems than those recruited as adults, according to a new report.

The public health charity Medact uses its report, published on Tuesday, to call for the minimum recruitment age to be raised to 18.

“Minimum age laws exist to protect children from smoking, drinking, driving and watching violent films,” said Dr David McCoy, director of Medact. “It’s time for the UK to fall in step with the vast majority of countries and raise the minimum recruitment age to 18.”

The UK is the only country in Europe, and only permanent member of the UN security council, to still allow recruitment from age 16. A nationwide poll in 2014 found that 77% of the general public support a rise in the recruitment age to 18.

The army’s policy of recruiting children has been strongly criticised by multiple UN and UK parliamentary bodies, child rights organisations and human rights groups.

Despite the criticism, Medact found child recruits to the British army are more likely to be deployed on the frontline. In Afghanistan, British soldiers who enlisted at 16 were approximately twice as likely to be killed or injured when compared with soldiers who enlisted when they were over 18.

Child recruits are also more vulnerable to suicide, self-harm, post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse than adult recruits, the report found.

Steve Brown joined the army cadets aged 13 in 1995 and the army three years later. “I became a child soldier in the British army because they’d groomed me since the moment I joined the cadets,” he said. “The army turned up every couple of months with motorcycle displays and other spectacles, and promised us life in the army would be glamorous, fun and well-paid. There was no mention of the downsides, even at the recruitment office itself.”

Brown left the army after his second tour of Iraq in 2006. Now 35, he struggles with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “A decade after leaving the army, I’m still recovering from the damage it did to me,” he said. “I joined straight out of school, so didn’t have a chance to become an individual. When I left, I realised that I had never learned how to make my own decisions or have my own opinions. Because I’d joined so young, I had been completely moulded by the army and life outside was almost impossible.”

Brown left the army after his second tour of Iraq in 2006. Now 35, he struggles with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “A decade after leaving the army, I’m still recovering from the damage it did to me,” he said. “I joined straight out of school, so didn’t have a chance to become an individual. When I left, I realised that I had never learned how to make my own decisions or have my own opinions. Because I’d joined so young, I had been completely moulded by the army and life outside was almost impossible.”

The army accepts applications from children aged 15 years and 7 months. In the last financial year, 22.2% of recruits were under 18. New recruits under 18 have to sign terms of service which can prevent them from leaving the army for up to six years.

McCoy said that how the UK armed forces recruits children breaches its own definition of “informed consent”. He said: “Full and informed consent of these children is not always gained. There are compliance issues with the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, which the UK has signed.”

Young veterans, aged 16-24, are more likely to kill themselves when compared with the general population: between 1984 and 2013, male soldiers aged under 20 were 47% more likely to kill themselves than the same age group in the general population. “These findings are mainly a result of a higher prevalence of pre-service vulnerabilities amongst young recruits to the armed forces,” the report said.

The report comes after the defence secretary, Michael Fallon, announced that cadet army units would be expanded in state schools. While the government argues that the cadet programme helps raise pupils’ attainment, campaigners have expressed fears that these units act as a channel of recruitment into the armed forces, and that military activities for children as young as 12 are inappropriate in the educational environment.

Citing evidence that military marketing strategies which glamorise war “take advantage” of the tendency of adolescents to be driven by immediate social rewards and risk-taking behaviours, the report also accuses the army of not being truthful enough about life in the military.

“The recruitment approach is designed to appeal to adolescent decision-making biases by portraying military life in glamorous terms whilst frequently using terms such as ‘big guns’, ‘awesome armour’ and ‘big boys’ toys’,” the report notes.

Recruitment materials “often fail to provide complete and accurate information about the terms and conditions of service for potential recruits”, the report says. They also don’t include information about the difficulties and long-term risks of an armed forces career while briefing materials for parents do not fully explain the demands or risks of military life.

“All too often, the claim is made that military life can be good for troubled adolescents,” said McCoy. “The argument is that the military can provide discipline and a sense of purpose for individuals who may be struggling with education, or who are engaged in self-harming or antisocial behaviour.

“There are two things wrong with this viewpoint. First, there is evidence that military life may be harmful to the health and wellbeing of those recruited as adolescents,” he said. “Second, there are other ways to support adolescents who are struggling with their education and social situation, and if the military is presented as the only viable option, then the recruitment of under-18s cannot be considered to be consensual.”

A Ministry of Defence spokesperson said: “The armed forces offer young people opportunities that aren’t available elsewhere, from basic literacy education and support for postgraduate degrees, to high-quality accredited training and unique employment prospects. Like everyone who serves our country, under-18s – who can only sign up with formal written consent of a parent or guardian – are fully supported throughout their service career.”

Wayne Sharrocks at 17 in 2006 in the Falklands. Photograph: Sharrocks family

Wayne Sharrocks at 17 in 2006 in the Falklands. Photograph: Sharrocks family

Case study: Wayne Sharrocks

My father was in the army but I didn’t consider it as a career until I was 15 and the Iraq war was happening. I was manipulated by the media: soldiers were always referred to as “heroes” and being in the army, fighting these terrorists, was presented as being the noblest thing a man could do. At 15, you desperately want to be a man. I was immature and naive: I didn’t even think about any of the realistic aspects of going to war and no one told me about them.

I tried to sign up at 15 but problems with my eyes meant I had to wait. I joined the day I turned 17. The manipulation started immediately: we were battered into following orders without thinking, the loyalty to our unit was absolute and – most psychologically damaging – we had our human instincts destroyed, so killing someone wasn’t a big deal and always being ready to fight was second nature.

If I’d been older, perhaps the training wouldn’t have affected me mentally in the way it did. But as a child, I accepted it entirely. My friends now say that I became hyper-aggressive and super-angry as a result of my army training. At the time, I thought that was a really good thing. As I say, I was a child. I had no wider experience of life to give me perspective. I was used by the army.

I decided to leave after seeing two colleagues seriously hurt and being badly hurt myself in Afghanistan in 2011. But I was still so brainwashed that it took me a couple of years to actually get out.

I spent the next few years in a terrible state. I’d lost my army family, my support system, my bubble of existence. The army promises you qualifications but they’re not transferable: I went from a position of responsibility in the army to spraying kitchen furniture as a civilian. There was nothing else I could do.

I eventually had a breakdown. I was going to ask the army to take me back: I thought I couldn’t survive outside it. But I’ve had counselling and am working my way back up. I’m 27 now. The army has taken 10 years of my life. And yes, I’m angry about that. Very angry.